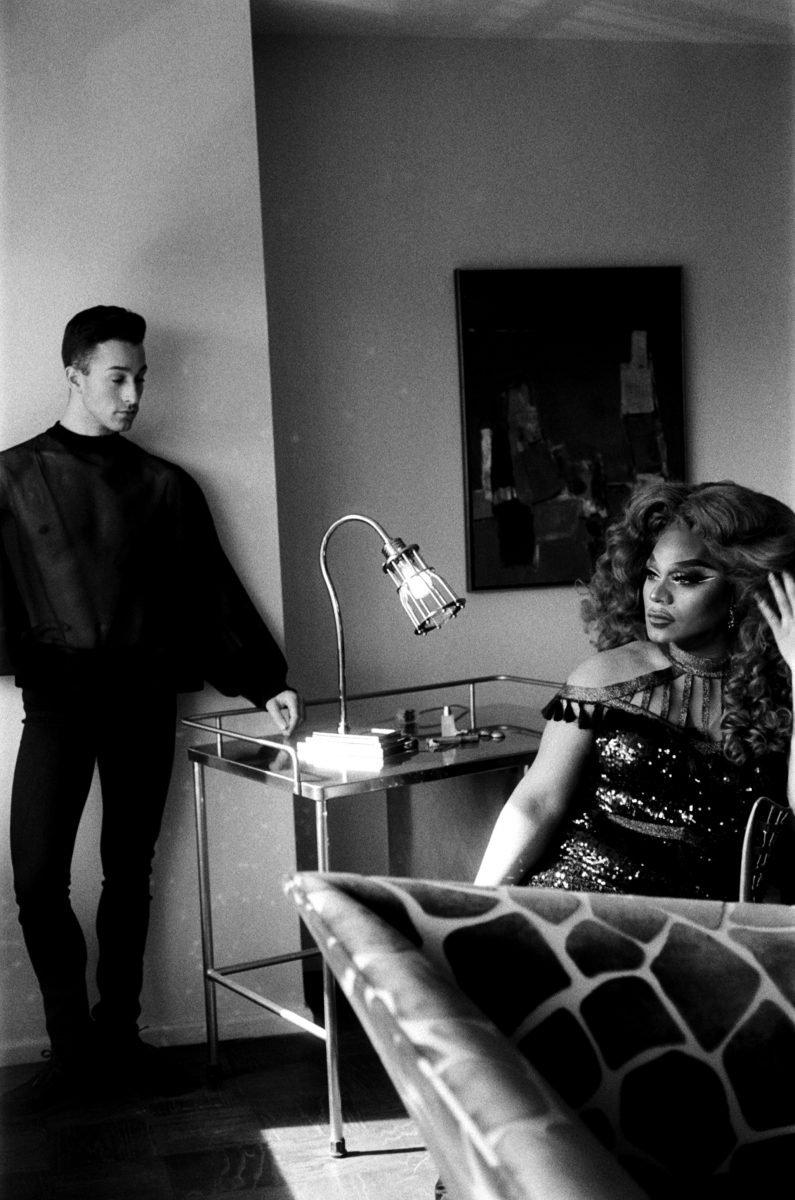

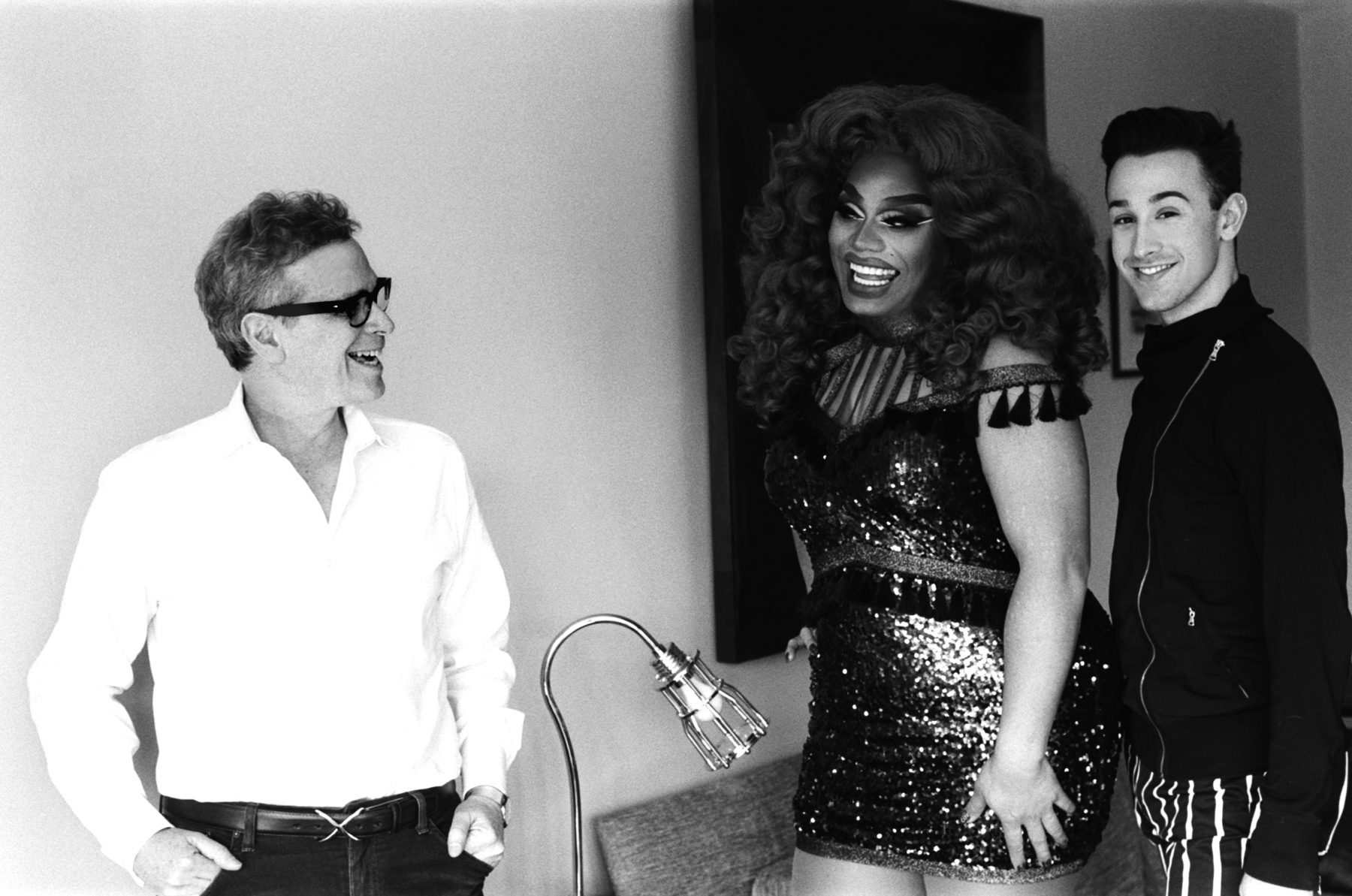

My interviews with a variety of creative icons is wrapping up on ASPIRE DESIGN AND HOME. In this series, I speak with creative talents in my life. We discuss how they approach their work. Maura Sullivan captures these moments with her iconic black and white photography. The photos and interviews can be found on ASPIRE DESIGN AND HOME’s website.

Below is more about singer/songwriter Jean Rohe.

Creative Icon Jean Rohe

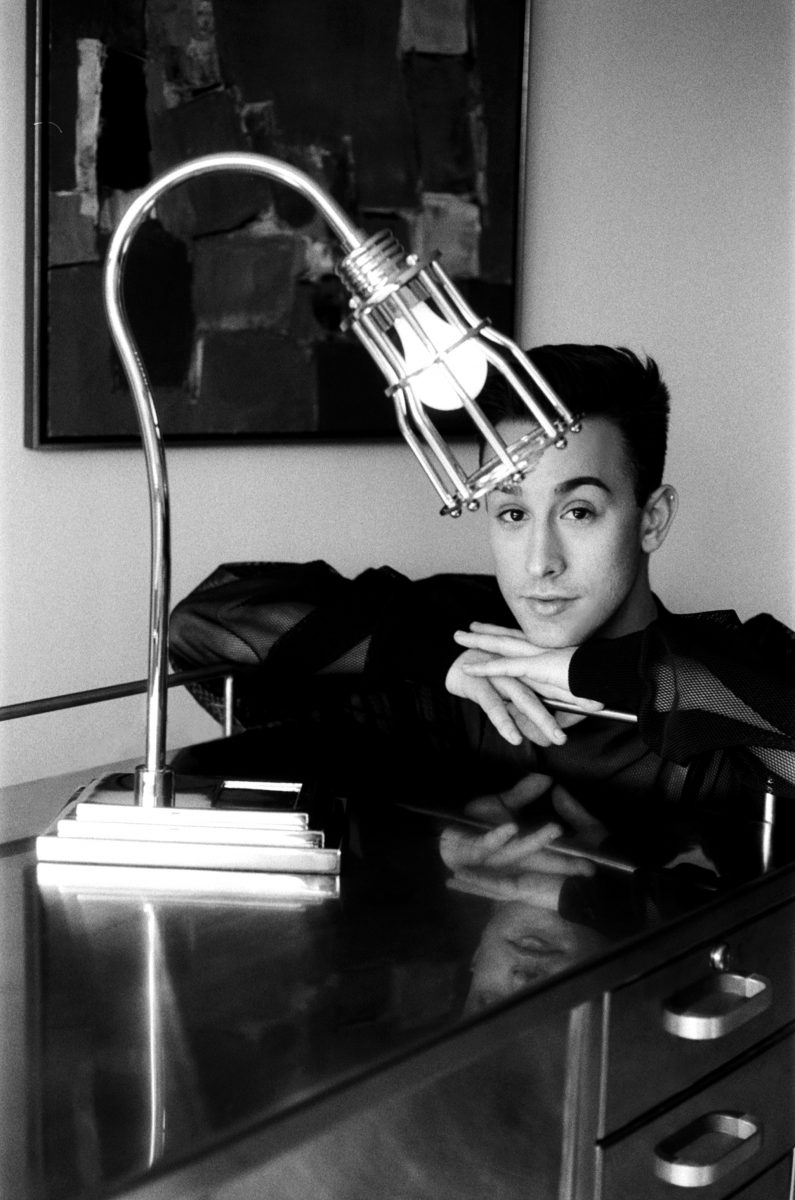

(Reeves desk lamp by Barry Goralnick for Currey & Co.; photo: Maura Sullivan)

Jean came into my life about five years ago. My husband and Jean shared a house for two weeks during the Johnny Mercer Writer’s Colony at Goodspeed Opera House. It was an extra-snowy few weeks, snowing them in and isolating them in East Haddem, CT – though nothing like what we’re all experiencing now. The group was extremely productive in their musical efforts and bonded instantly during these two weeks. I heard all about the wonderfully talented Jean Rohe.

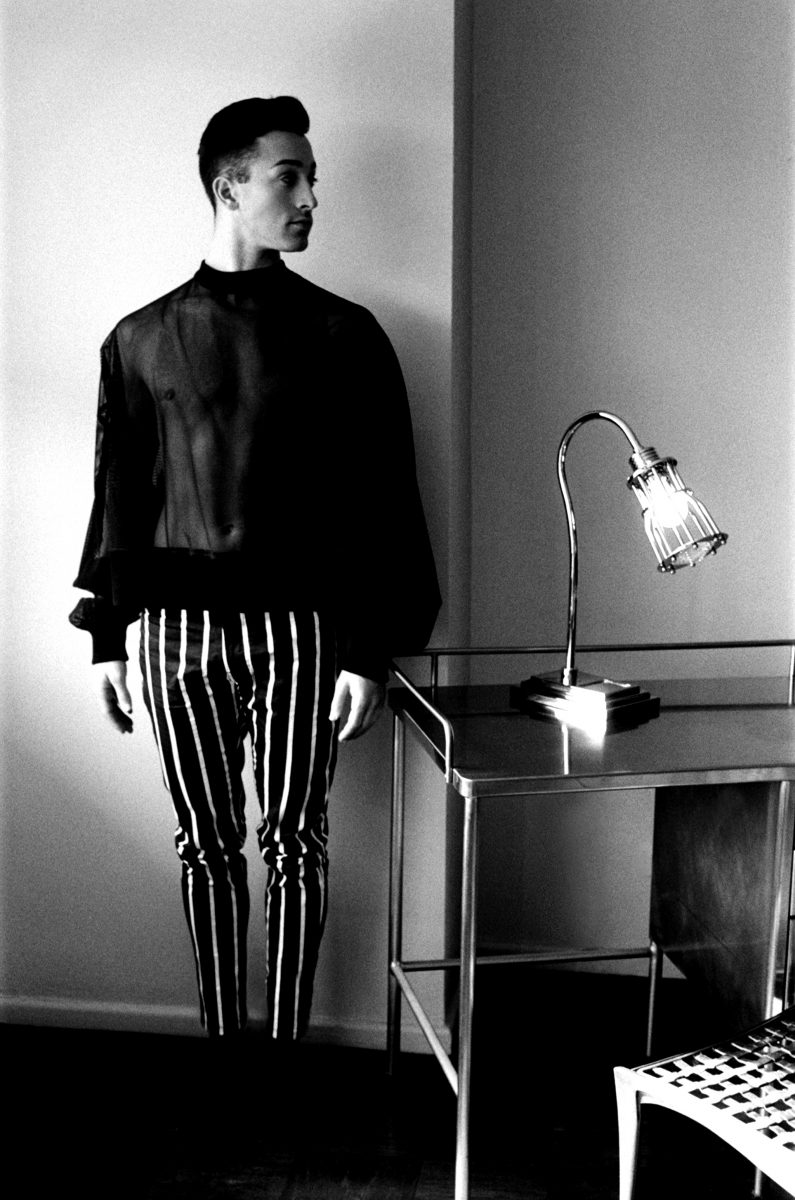

(Davy desk lamp by Barry Goralnick for Currey & Co.)

Later that Spring, Jean came to our home for a vegetarian meal. We had a great time and I expanded my cooking repertoire, trying out a few new dishes. Though I’m not vegetarian, Jean’s commitment to it and the individual impact we all have on our world through the choices we make is inspiring. While she is committed to some lofty ideals, she is also a fun and delightful person (I think you can tell from the photos of us together).

Jean not only writes evocative songs, she lives by her principles and is vocal about sharing her beliefs. She is the personification of belief into action. And this comes through in her artistic work loud and clear. Her inspiring, thought-provoking Nation Anthem: Arise! Arise! is the perfect example (watch the video – trust me, you’ll be moved).

While Jean’s songs and recordings are wonderful, her live performances are even more extraordinary. I will never forget seeing Jean perform her piece The Odysseus Agreement at National Sawdust (a very cool venue in Brooklyn).

I do believe that art can change the world, and in these times, it’s especially inspiring to know Jean Rohe – her personal approach and dedication to her art, and to improving our world. She is the embodiment of the sort of creativity-with-positive-purpose we need now more than ever.

You can read my interview with Creative Icon, Jean Rohe on ASPIRE DESIGN AND HOME here.